This was part of my essay for a class on Language Policy and Planning. The essay was marked with a distinction. I’m publishing a part of the essay for Buwan ng Wika.

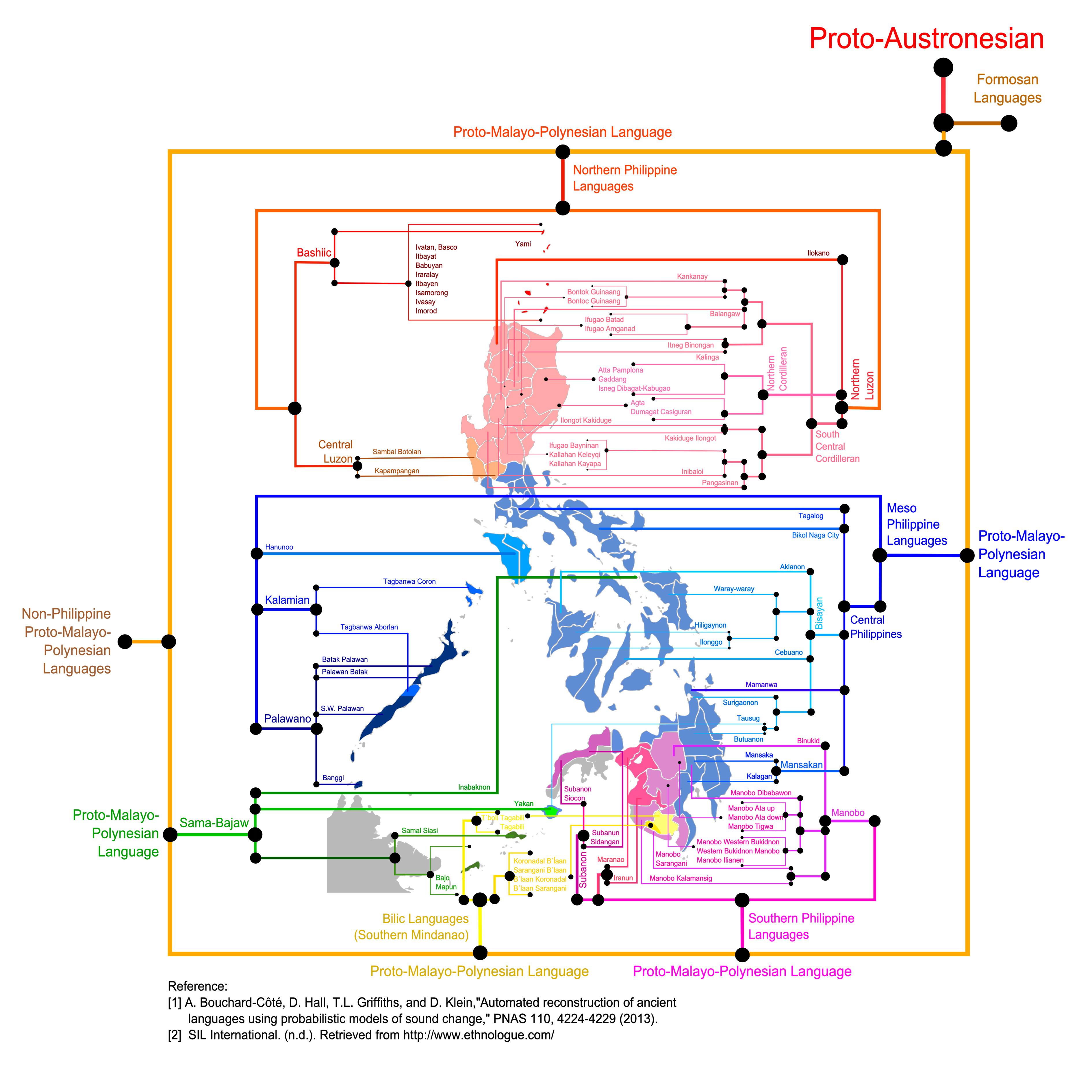

The Department of Education now has 17 designated languages that qualify for mother-language based education. The current Philippine constitution (1987) states that the national language is Filipino and as it evolves, “shall be further developed and enriched on the basis of existing Philippine and other languages.” Further, the Philippine constitution (1987) has mandated the Government to “take steps to initiate and sustain the use of Filipino as a medium of official communication and as language of instruction in the educational system.”

However, this current policy on language has changed over the century, largely due to the Spanish, American, and Japanese colonisation, the liberation, and changes in the constitution post-dictatorship. There also remains to be contentions on whether Filipino, based on the Tagalog language, should be the national language of the Philippines. These contentions come from the non-Tagalog speaking region that have called the current language policy as “Tagalog imperialism.”

Given the rich history of the country and controversies regarding its language planning and policy throughout the century, this essay aims to explore the history of language policy and planning in the Philippines and the impacts it has had on its people, especially the non-Tagalog/Filipino speaking population. Secondary research and analysis will be used as a method of research.

History of LPP in the Philippines

The Philippines’ national language is Filipino. As mentioned earlier, de jure, it is a language that will be enriched from other languages in the Philippines. De facto, it is structurally based on Tagalog, the language of Manila and the CALABARZON (Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Quezon) region (Gonzalez, 2006).

SPANISH COLONISATION

What was the language policy and planning like during the Spanish colonisation? According to Rodriguez (2013), the Spanish Crown issued several contradictory laws on language: missionaries were asked to learn the vernacular but were then required to teach Spanish. The friars continued to learn the local languages for evangelisation which turned out to be a success (Gonzalez, 2006). Thus, teaching Spanish teaching remained limited for the elites and wealthy Filipinos ready to conform to Spanish colonial agendas (Martin, 1999).

This was a way for the Spanish to control the country, and as Mahboob and Cruz (2013) suggest, a means to divide the rich and the poor. Arguably, this can also be the reason why the ilustrados (Filipinos educated in Spain) supported Philippine independence. Gonzalez (2006) writes,

In spite of repeated language instructions From the Crown on teaching the natives the Spanish language, there was only a little compliance. Instead the friars using common sense, kept employing the local languages, so much that in the period of intense nationalism in the nineteenth century, the failure of the Spanish friars to teach Spanish was used by some of the ilustrados (Filipinos educated in Spain) as a reason to accuse the friars of deliberately keeping Spanish away from the natives so as to prevent them from advancing themselves.

Gonzales, 2006

AMERICAN COLONISATION

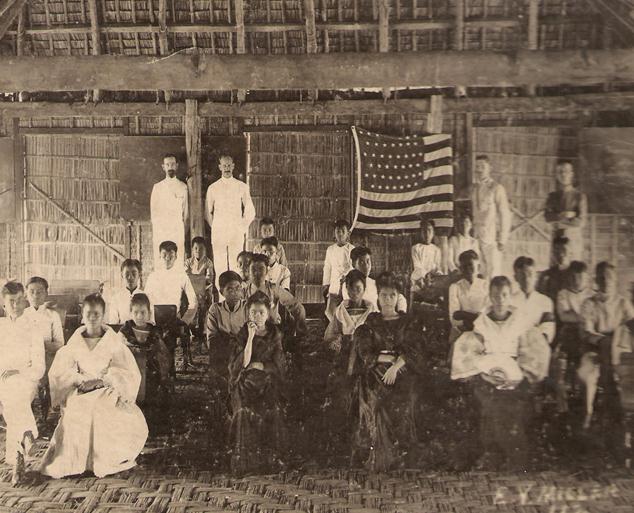

Shortly after the independence from Spain, the Philippines came under the American rule from 1898-1946. In the beginning Filipinos saw Americans as allies against Spain. The Americans saw the perfect opportunity for colonisation that Spain did not: education. While the Spanish eventually established schools through the Royal Decree of 1863, these were literacy schools teaching reading and writing in Spanish, religious studies, and numeracy not leading to any degrees (Gonzalez, 2006). Martin (1999) notes that the Americans, on the other hand, saw education as a powerful weapon and in the Philippines they found subjects receptive to the opportunities given by the English language. Gonzalez (1980, p.27-28) writes, “the positive attitude of Filipinos towards Americans; and the incentives given to Filipinos to learn English in terms of career opportunities, government service, and politics.”

American policy allowed for compulsory education for all Filipinos in English but was hostile to local languages. Although President McKinley ordered the use of English as well as mother tongue languages in education, the Americans found Philippine languages too many and too difficult to learn thus creating a monolingual system in English (Gonzalez, 2006). Manhit (1980) notes that during this time, students who used their mother tongue while in school premises were imposed with penalties. Media of instruction were in English, teachers were trained to teach English, and instructional materials were all in English. Local languages were used as “auxiliary languages to teach character education, good manners, and right conduct” (Martin, 1999, p.133). Ricento (2000 p. 198) argues that LPP during American colonisation led to a “stable digglosia” where English became the language of higher education, socioeconomic, and political opportunities still visible today.

Constantino (2002, p. 181) writes about how the acceptance of the English language eventually allowed Filipinos to embrace colonialism:

The first and perhaps the masterstroke in the plan to use education as an instrument of colonial policy was the decision to use English as the medium of instruction. English became the wedge that separate Filipinos from their past and later was to separate educated Filipinos from the masses of their countrymen… With American textbooks, Filipinos started learning not only a new language but also a new way of life, alien to their traditions and yet a caricature of their model. This was the beginning of their education. At the same time, it was the beginning of their miseducation, for they learned no longer as Filipinos but as colonials.

Constantino, 2002

INDEPENDENCE

With the Commonwealth constitution being drafted, then Camarines Norte representative Wenceslao Vinzons proposed to include an article on the adoption of a national language. Article XIII section 3 of the 1935 Commonwealth Constitution directed the National Assembly to “take steps toward the development and adoption of a common national language based on one of the existing native languages.” In 1936, the Institute of National Language (INL) was founded to study existing languages and select one of them as the basis of the national language. In 1937, the INL recommended Tagalog as the basis of the national language because it was found to be widely spoken and was accepted by Filipinos and it had a large literary tradition. By 1939, it was officially proclaimed and ordered to be disseminated in schools and by 1940 was taught as a subject in high schools across the country.

There was resistance to Tagalog, especially among speakers of Cebuano (Baumgartner, 1989). Baumgartner (1989, p.169) summarises the sentiments of other ethnic groups and asks, “With what right could the language of one ethnic group, even if that ethnic group lived in the national capital, be imposed on others?” Hau and Tinio (2003), however, point out that this opposition to Tagalog was not a manifestation of an ethnic conflict but rather reflects battles over resource allocations parceled out by regions. This has led for anti-Tagalog forces to ally themselves with the pro-English lobby (Lorente, 2013).

60’s and 70’s

The 60’s and the 70’s saw nationalist movements critical of the English language (Mahboob and Cruz, 2013). However, English remained a dominant language even at the peak of linguistic nationalism and height of student activism in the 70’s (Hau and Tinio, 2003). In 1974, a Bilingual Education Policy (BEP) was formally introduced, using English for Science and Mathematics and Filipino for all other subjects taught in school (Lorente, 2013). Gonzalez (1998) notes that this was a compromise to the demands of both nationalism and internationalism: English would ensure that Filipinos stay connected to the world while Filipino would help in the strengthening of the Filipino identity. This had little success, with English still dominant and Filipinos feared an “English deprived future.”

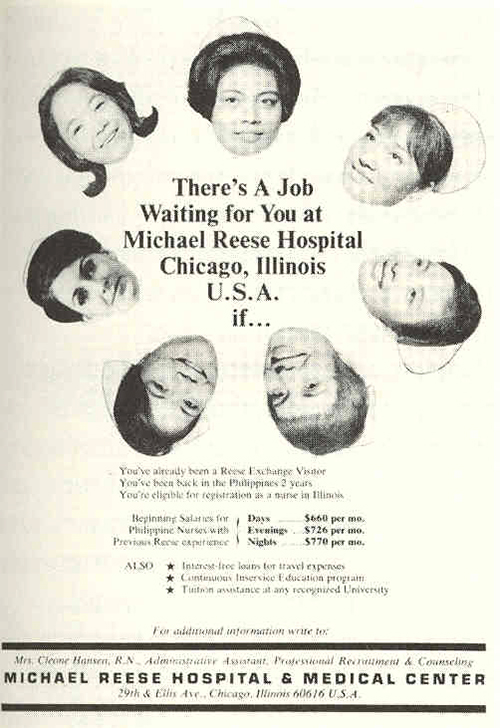

The year 1974 saw the start of the Philippines adhering to neoliberal policies, where the government started to promote cheap labour to other countries, advertising Filipinos’ ability to speak English. This was the year the first batch of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW) was deployed to the Middle Least. An advertisement in The New York Times said: “We like multinationals … Local staff? Clerks with a college education start at $35 … accountants come for $67, executive secretaries for $148 … Our labor force speaks your language” (Lorente, 2013).

The 70’s, which was also the time of the dictatorship in the Philippines, saw changes in the education system, restructured to answer to export-oriented industrialisation (Lorente, 2013). With cheap export labour in mind, then President Ferdinand Marcos had a strong support for English and shifted English education to vocational and technical English training (Tollefson, 1991).

POST-DICTATORSHIP

After the dictatorship, the 1987 Constitution was written. Tagalog was changed to Pilipino and then Filipino for it to be less regionalistic, or less connected to the Tagalog region. According to this Constitution, Filipino was to be developed from all local languages of the Philippines.

According to this new BEP, Filipino and English shall be used as the medium of instruction while regional languages shall be used as auxiliary media of instruction and as initial language for literacy. Filipino was mandated to be the language of literacy and scholarly discourse while English, the “international language” of science and technology. However, nothing changed and implementation of the policy failed at most levels of education (Bernardo, 2004).

In 1991, the Komisyon ng Wikang Filipino (Commission on the Filipino Language) was established. They have led the celebration of Buwan ng Wika (National Language Month) every August. It is a regulating body whose job includes developing, preserving, and promoting the various local Philippine languages. The commission has published dictionaries, manuals, guides, and collection of literature in Filipino and other Philippine languages.

Both English and Filipino have dominated the education system in the Philippines. English is seen as the language of opportunities, and have been used by Filipinos to work abroad and find opportunities in the age of globalisation. Filipino, on the other hand, is seen as the language that can give identity to Filipinos, although not everyone agrees.

Will English and Filipino continue to dominate the country? With the current ideologies and policies put in place, it will. However, as other language speakers continue to fight for their identity and the right to be taught in their mother tongue, we might be able to see some changes, allowing for recognition of other languages in the country, and maybe even be given the same status as English and Filipino.

2 Replies to “A History of the Philippines’ official languages”

Comments are closed.